Introduction

Sanskrit words and sentences undergo many different kinds of sound changes. Vowels might combine or become consonants. Consonants might shift from one class to another. And even more extensive transformations are possible. Together, these sound changes are called sandhi.

Many Sanskrit students learn a basic version of sandhi in the course of their studies. But Pāṇini is not content with modeling the basics. Instead, his goal is to model all of Sanskrit's sandhi rules as fully as he can. And to do so, he creates several devices that let him express these rules clearly and concisely.

In this unit, we will learn about the specific techniques and devices that Pāṇini uses to model Sanskrit's sounds and sandhi rules. Starting from scratch, we will build up his core system step by step. And by the end, we will have a simple but complete system that contains most of the Aṣṭādhyāyī's essential components. Once we have that basic system in hand, we can explore the rest of the grammar and see how the Pāṇinian system works in practice.

Sounds for beginners

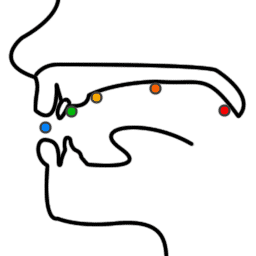

Most Sanskrit sounds are pronounced with five places of articulation within the mouth. You can see these five points marked in the image below:

From right to left, these five points are:

the soft palate

the hard palate

the alveolar ridge

the base of the teeth

the lips

All of the sounds below are colored according to which place of articulation they use. Sounds that use multiple places of articulation, or that use places of articulation other than the five above, are left black.

First are the vowels. The first nine vowels are called simple vowels:

- अ

a - आ

ā - इ

i - ई

ī - उ

u - ऊ

ū

- ऋ

ṛ - ॠ

ṝ - ऌ

ḷ

And the others are called compound vowels since they are made from combinations of the simple vowels:

- ए

e - ऐ

ai - ओ

o - औ

au

Of these vowels, five (a, i, u, ṛ, ḷ) are called short. The others are called long and are pronounced for twice the duration of the short vowels. There is also a third length, pluta (prolated), that is much longer and much rarer.

All Sanskrit vowels can take one of three accents: udātta (high), anudātta (low), and svarita (mixed). And they can be either nasal or non-nasal. So each of the vowels above has 3 × 2 = 6 variants.

Next, we have the first twenty-five consonants.

- क

ka - ख

kha - ग

ga - घ

gha - ङ

ṅa

- च

ca - छ

cha - ज

ja - झ

jha - ञ

ña

- ट

ṭa - ठ

ṭha - ड

ḍa - ढ

ḍha - ण

ṇa

- त

ta - थ

tha - द

da - ध

dha - न

na

- प

pa - फ

pha - ब

ba - भ

bha - म

ma

This is a grid with five rows and five columns. Each row in the grid uses a different place of articulation, and each column encodes different properties:

The first two columns (ka, kha) are unvoiced sounds, meaning that we pronounce them without using our vocal cords. (Compare “p” and “b” in English.) All the others are voiced. Vowels are also voiced.

The second and fourth columns (kha, gha) are aspirated sounds, meaning that we pronounce them with an extra puff of air. All the others are unaspirated.

The fifth column (ṅa) contains nasal consonants, and the other columns contain stop consonants.

Next are the semivowels, which have a close relationship to the vowel sounds. All of them are voiced:

- य

ya - र

ra - ल

la - व

va

(Technically, va uses two points of pronunciation. But this is a minor detail, and it can essentially be treated as if pronounced only with the lips.)

Finally, we have the sibilants. ha is voiced, but the rest are unvoiced:

- श

śa - ष

ṣa - स

sa - ह

ha

Sandhi for beginners

When sounds are pronounced continuously, they can change each other's pronunciation. Sandhi is the name for these sound changes.

Most sandhi changes are between two sounds that appear next to each other in continuous speech. Here are some examples of common sandhi changes:

इ + उ → यु

i + u → yuअ + इ → ए

a + i → eक् + अ → ग

k + a → ga

Some sandhi changes are optional and are applied at the speaker's preference. Also, sandhi changes might be allowed or blocked in different environments, such as:

at the end of a word

at the end of a word that expresses the dual number

at the end of specific words

at the end of a verb prefix

In other words, sandhi changes are not purely phonetic. We must also understand what is being said so that we can apply sandhi changes correctly.