Starting Out

Introduction

This unit of the guide, called Starting Out, covers the most basic and common parts of Sanskrit grammar. Consider the first two verses of the Bhagavad Gita:

धर्मक्षेत्रे कुरुक्षेत्रे समवेता युयुत्सवः ।

मामकाः पाण्ड्वाश्चैव किमकुर्वत संजय ॥dharmakṣetre kurukṣetre samavetā yuyutsavaḥ ।

māmakāḥ pāṇḍvāścaiva kimakurvata saṃjaya ॥दृष्ट्वा तु पाण्डवानीकं व्यूढं दुर्योधनस् तदा ।

आचार्यम् उपसंगम्य राजा वचनम् अब्रवीत् ॥dṛṣṭvā tu pāṇḍavānīkaṃ vyūḍhaṃ duryodhanas tadā ।

ācāryam upasaṃgamya rājā vacanam abravīt ॥

By the end of Starting Out, you will be able to read all of the highlighted words in Devanagari (or IAST, if you like), understand their meanings and use, and perfectly explain how they are formed. Pause to realize how remarkable this is: in just a few lessons, you will perfectly understand everything there is to know about these words.

But of course, you will be able to read much more than just a few words! As we develop our Sanskrit ability, we will start to read lines and sentences from many sorts of Sanskrit texts.

Grammar

As mentioned earlier, a thorough understanding of the sounds in Sanskrit is vital to understanding Sanskrit itself. Sanskrit's vowels and consonants are all involved in regular and ordinary changes that can significantly alter the meaning of a sentence. These changes are all part of a larger set of rules, which is simply known as Sanskrit's grammar.

If you already know what "grammar" is, you can skip this paragraph. But if you do not, I will explain it now. "Grammar" refers to the rules and patterns of a language. Grammar describes both how words are made and how words are put together. Grammar also describes what words mean when they are put together, and it describes how certain combinations of words create new meanings. After all, a language is a way for us to express and share our ideas. Without some common rules and patterns, it becomes hard to understand what another person says or writes. Words that follow the rules of grammar are called grammatical.

Still, what is meant by "Sanskrit" grammar? What makes Sanskrit different from languages like English?

An Overview of Sanskrit Grammar

Sanskrit Word Order

Let's look at a basic English sentence:

- Elephants eat fruits.

When we read this sentence, we automatically assign different meanings to the different words. Here, "elephants" is the thing that eats the fruit. A word like this is called the subject. The second word, "eat," is the action that the subject does. A word that describes the subject's action is called the verb. The last word, "fruits," is the thing that the subject eats. The thing that the subject affects the most with his action is called the object.

- Elephants eat fruits.

Subject Verb Object

So, we have subjects, verbs, and objects. In a typical English sentence, the subject comes first, the verb comes in the middle, and the object comes last. We can say that English is mostly in "subject-verb-object" order, or "SVO" for short. Other SVO languages include Arabic, Chinese, Finnish, Russian, and Thai.

But not all languages follow the SVO pattern. We also have VSO (e.g. Classical Arabic and Hebrew, Irish), VOS (e.g. Fijian, Mayan languages), OSV (e.g. Xavante), OVS (sometimes in Finnish, German, and Hungarian), and SOV (e.g. Hindi, Japanese, Korean, Latin, Mongolian, Nepali, Persian, Quechua). Sanskrit is an SOV language. So are almost all other Indian langauges.

Let's look again at the example above and compare the English and Sanskrit versions of the sentence:

- Elephants eat fruits.

Subject Verb Object - gajāḥ phalāni khādanti

Subject Object Verb

Although Sanskrit is an SOV language, Sanskrit word order is not as fixed as it is in English, and SOV is more of a common practice than a strict rule. How can this be? The answer is this: because of Sanskrit's grammatical structure, words carry extra information with them. Because of this extra information, word order is more flexible in Sanskrit than in English.

We can rearrange the Sanskrit words above in any order we like; our result will still be a grammatical sentence. Let's rearrange the words in "Elephants eat fruits" and see how English and Sanskrit react.

- Fruits eat elephants.

Subject Verb Object - phalāni khādanti gajāḥ

Object Verb Subject

Notice that the English example loses its meaning when we rearrange the words. In fact, the new sentence is completely different! The subject has become the object, and the object has become the subject; this makes it look like the fruits are the ones doing the eating! But in Sanskrit, it's OK to rearrange the words in a sentence, at least most of the time. In this sentence, the original idea of elephants eating fruit still remains.

Now we have two questions to consider:

- If Sanskrit word order is flexible, then does it matter which word order we use?

- What information do Sanskrit words contain that English words do not?

Word order adds emphasis

When we change the order of words in a Sanskrit sentence, the original idea is still there. However, the first word of a sentence usually has the most emphasis, meaning that it's the word we should pay attention to the most. Consider the two sentences below. Both sentences use the same words. The difference between them is that they use different word orders. The word order slightly changes the meaning of the sentence.

- tvām pṛcchāmi

You I-ask — It is you that I ask.

- pṛcchāmi tvām

I-ask you — I ask you.

Word order acts similarly in other Indo-European languages, like Greek. Consider the first lines of the Iliad and the Odyssey, the two main Ancient Greek epic poems.

- Μῆνιν ἄειδε, θεά, Πηληιάδεω Ἀχιλῆος (Menin aeide, Thea, Peleiadeo Achileos)

[Rage sing, Goddess, of-the-son-of-Peleus of-Achilles]

Rage — Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus' son Achilles. The Iliad (translated by Robert Fagles) - Ἄνδρα μοι ἔννεπε, Μοῦσα, πολύτροπον … (Andra moi ennepe, Mousa, polutropon, hos mala polla)

[Man me tell, O-Muse, the-much-twister who very in-many-ways.]

Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns …The Odyssey (translated by Robert Fagles)

The Iliad, a story of war and Achilles' rage, fittingly starts with the word "rage." The Odyssey, a story of a man's long journey home, fittingly starts with the word "man."

Inflection adds information

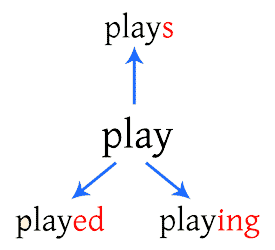

The word "play" and its behavior in English.

Inflection is the way a basic word starts to carry more information about what it means in a sentence. We inflect words by taking smaller words and slightly changing them. English does not have much inflection left, but we can still see it in some places.

For example, we can see inflection in the word "play." We say "I play" and "you play," but we say "he plays," not "he play." This is inflection! The word "play" changed a little bit to show that the subject is "he," "she," or "it," instead of "I" or "you." So, if we saw just the word "plays," we could guess that the original subject was "he," "she," or "it."

Let's look at "play" again. We say "I play" and "I will play," but we say "I played." This is inflection again! The word "play" changed to show that the action has already happened. We can work backward from the word "played" and figure that out. Meanwhile, "I will play" shows no inflection at all: "play" does not change, and we can't work backward from just "play."

It is important to realize that an inflected word is still one word. Sanskrit, like most Indo-European languages, uses inflection to a far greater extent than English does. In Sanskrit, a complex idea can exist as one word and still carry a single and precise meaning. For example, ideas like "from the two villages" (Sanskrit grāmābhyām) and "they will want to go" (Sanskrit jigamiṣiṣyanti) are each inflected versions of simpler words (grāma, gam).

But are inflected languages preferable to non-inflected ones? I think the difference between them is only one of personal taste. More inflected languages are called synthetic languages, and you can click here to read more about them. Less inflected languages are called analytic languages, and you can click here to read more about them. Many languages, like English and Japanese, have features of both.

Review

In this lesson, we've learned the following terms:

- Term

- Definition

- grammar

- The set of rules that describes or defines a language

- grammatical

- used to describe an expression that follows the rules of grammar.

- subject

- In a sentence, the thing that performs an action

- verb

- In a sentence, the word that describes the action

- object

- In a sentence, the thing that is affected by the action

- emphasis

- a quality that tells us to pay attention to certain words

- inflection

- the act of changing a word to further clarify its meaning