Sanskrit in 5 minutes

In this short lesson, we hope to give you a basic feeling for what Sanskrit is like, so you can understand the kinds of questions that the Ashtadhyayi aims to answer.

The alphabet

Sanskrit is written phonetically. Each sound has one symbol, and each symbol corresponds to one sound.

The sounds below are provided in both Devanagari (संस्कृतम्) and romanized Sanskrit (saṃskṛtam). All of the Devanagari text that appears in these lessons will also be in romanized Sanskrit.

First are the vowels. Nine vowels are called simple:

- अ

a - आ

ā - इ

i - ई

ī - उ

u - ऊ

ū

- ऋ

ṛ - ॠ

ṝ - ऌ

ḷ

And four are called compound vowels, since they are made from combinations of simple vowel sounds:

- ए

e - ऐ

ai - ओ

o - औ

au

Of these, five (a i u ṛ ḷ) are called short. The others are called long and are pronounced for twice the duration of the short vowels.

Next are two special sounds called the anusvāra and the visarga, respectively:

- अं

aṃ - अः

aḥ

Then come the stop and nasal consonants, which are pronounced by obstructing the flow af air through the mouth:

- क

ka - ख

kha - ग

ga - घ

gha - ङ

ṅa

- च

ca - छ

cha - ज

ja - झ

jha - ञ

ña

- ट

ṭa - ठ

ṭha - ड

ḍa - ढ

ḍha - ण

ṇa

- त

ta - थ

tha - द

da - ध

dha - न

na

- प

pa - फ

pha - ब

ba - भ

bha - म

ma

Then the semivowels:

- य

ya - र

ra - ल

la - व

va

And the sibilants:

- श

śa - ष

ṣa - स

sa - ह

ha

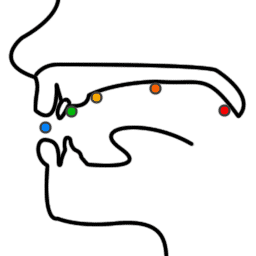

The sounds above are colored according to the point of articulation they use in the mouth. From right to left, these five points are:

the soft palate

the hard palate

the alveolar ridge

the base of the teeth

the lips

The details of pronunciation are part of śikṣā (phonetics), not vyākaraṇa. But all vyākaraṇa students are expected to have totally mastered śikṣā first.

This raises the questions: which phonetic distinctions are relevant and important in grammar, and how can we make those distinctions optimally?

Sandhi

In every spoken language, native speakers make subconscious changes to their speech so that they can speak more quickly and fluently. These changes are called sandhi.

Sanskrit sandhi changes are extensive. They occur both within words and between words. This raises the question: which sandhi changes apply in which contexts?

Inflection

Inflection is when we change part of a word to express a new meaning. English uses inflection in a limited way: we have one cat but two cats. Perhaps you will sleep today but slept yesterday.

Sanskrit uses inflection much more extensively:

नयसि नीयेरन् नेष्यताम् निनीषन्तः

nayasi

You lead

nīyeran

They might be led.

neṣyatām

of those about to lead

ninīṣantaḥ

those who want to lead

and in much more elaborate patterns, with multiple sandhi changes:

लभे रुणध्मि

labhe

I obtain.

ruṇadhmi

I obstruct.

This raises the question: Which inflectional patterns apply in which contexts, and with what semantics?

Sentences

Because Sanskrit word order is highly inflected, Sanskrit does not usually depend on a specific word order. For example, the two sentences below have the same semantics:

रामो रावणं हन्ति रावणं रामो हन्ति

rāmo rāvaṇaṃ hanti

Rama kills Ravana.

rāvaṇaṃ rāmo hanti

Rama kills Ravana.

Rather than word order, the Ashtadhyayi focuses on a more general question: how do words with different semantics combine to express sentence-level semantics?

The human constraint

The Ashtadhyayi is part of a culture that values oral tradition and memorization. So another important question it tries to address is a pragmatic one: how can this system be compressed to the smallest possible form, so that it is easy to memorize and easy to recall?